By Priest Paul Siewers, Ph.D.

Bucknell University

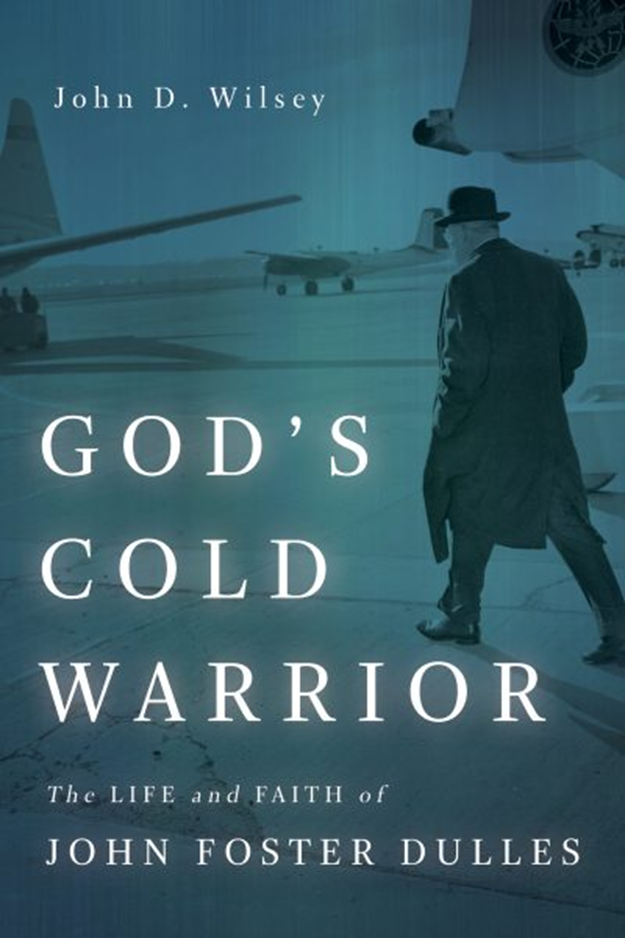

A recent book on former U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles displays an epic cover photo of him striding across an airport tarmac toward a plane, confidently bound for some diplomatic or covert mission against Communism, clad in a homburg hat and long coat, his uniform as a liberal American churchman and statesman. The book, God’s Cold Warrior by John D. Wilsey, examines the religious motivations for Dulles’ leadership of America’s side in the Cold War in the 1950s.

While the global jetsetter Dulles is perhaps best known today for the D.C. airport that appropriately bears his name, in the 1950s he arguably became the elder statesman of American civil religion in its battle against atheistic Communism during the heroic era of the Cold War. He presided over initiatives such as the formation of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), while laying the groundwork for the Vietnam War, and expanding NATO into West Germany in its first major enlargement. He did so with a soberly righteous air of belligerence. Winston Churchill famously observed that Dulles was the only bull he knew who carried his own china shop around with him.

But, long before, Dulles had championed the modernist faction in what became the major Presbyterian denomination in the U.S. (the Presbyterian Church USA) to victory over the “fundamentalist” faction of old-school Presbyterians. The latter faction coincidentally had been led by another one-time U.S. Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan. But Bryan was removed from the controversy by his death soon after the famous Scopes “monkey trial,” in which he successfully defended biblical beliefs about Genesis while being portrayed in the news media as having been out-classed by Clarence Darrow. Dulles in the 1920s successfully led the campaign for the right for clergy in his denomination to have the freedom not to believe in the Virgin Birth of Christ and the redemptory substance of the Crucifixion. He was also active in U.S. interfaith efforts that became the National Council of Churches. Yet in contrast to, or perhaps because of, the nature of his religious role, Wilsey’s book reports how, in the same inter-war era, Dulles came to prefer golfing and sailing to attending Sunday worship, despite his later reputation as helping President Dwight Eisenhower promote “Judeo-Christian values” in the war against Communism.

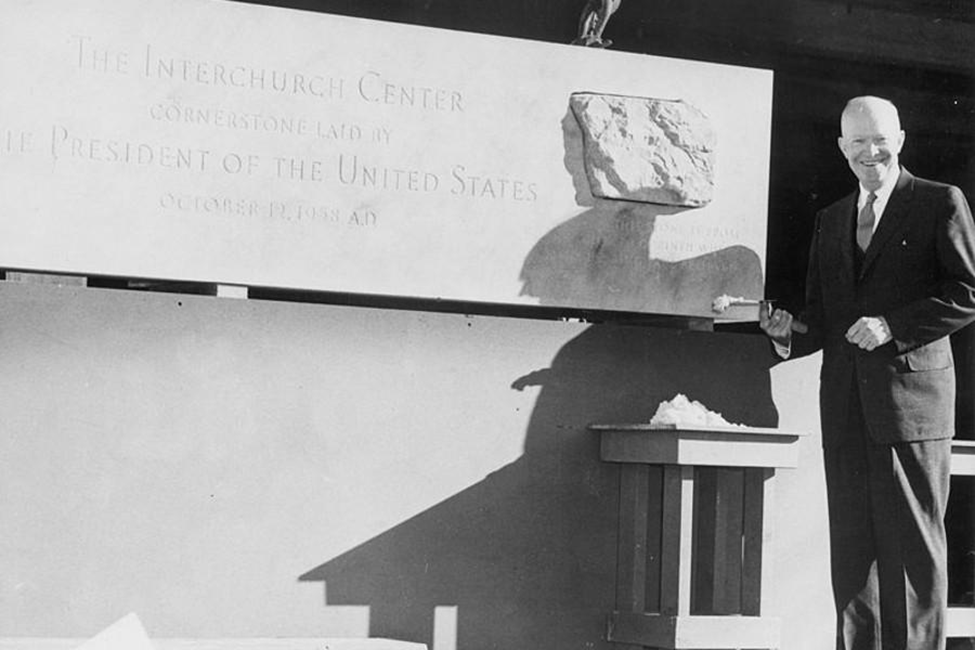

(Above) U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower lays the cornerstone for the Interchurch Center in New York City, headquarters for the National Council of Churches in 1958, as part of the campaign by Eisenhower and his Secretary of State Dulles to mobilize “Judeo-Christian values” against atheistic Communism.

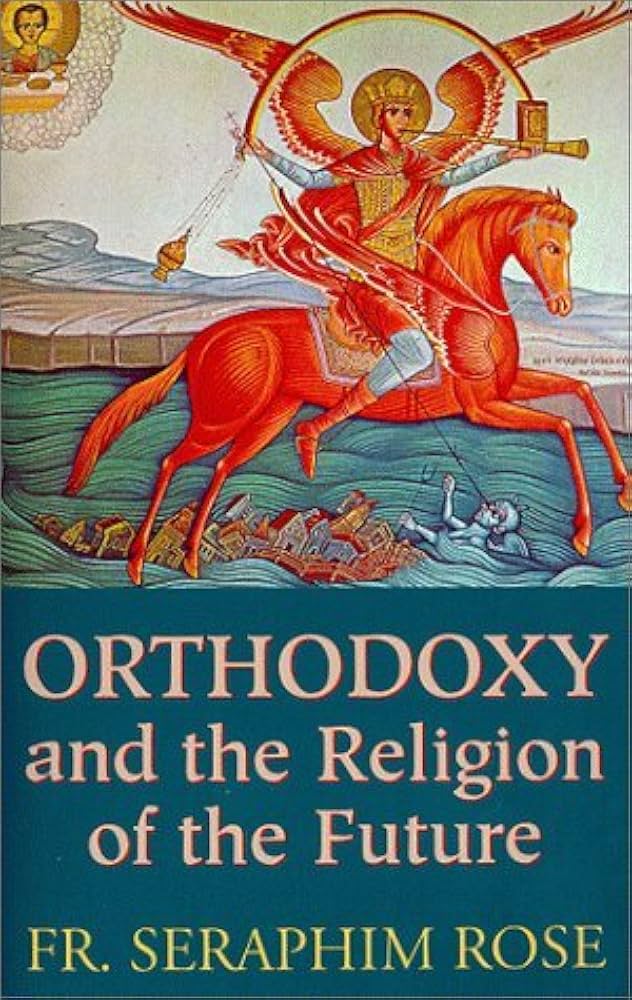

It will be argued here that the same anticommunist American civil religion that emerged in the 1950s with Dulles as champion ironically helped provide the basis for the emergence of a new ecumenist global spirituality in subsequent decades. The latter is outlined, from an Orthodox Christian perspective, by Hieromonk Seraphim Rose of blessed memory in his well-known book Orthodoxy and the Religion of the Future, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. That landmark study characterized an emerging “New Age” spirituality as a global movement hostile to traditional Christianity, and presaging scriptural cautions about the religion of “anti-Christ.” The Evangelist John had characterized the “spirit of anti-Christ” as denying the actual Incarnation of Jesus Christ (and, Orthodox Christians might add, the historic Church as the Body of Christ). Admittedly, the argument of this article may seem like nit-picking in the historical context, when Dulles and others confronted an atheistic system responsible for tens of millions of deaths, many of them Orthodox Christians. There is no equivalency in that sense at all. Yet arguably, as the modern Catholic writer J.R.R. Tolkien pointed out in The Lord of the Rings, in opposing evil there is always the risk of becoming like it. As Alexander Solzhenitsyn noted in his later writings, the positioning of Western mainstream culture vis-a-vis traditional Christianity had its own subtler, deceptively appealing, and longer-lasting opposition, with an often hidden and thus sometimes even more dangerous toxicity from a spiritual standpoint. It is this tendency that is explored here, in anniversary homage to Hieromonk Seraphim’s groundbreaking 1975 book.

ROOTS OF COLD WAR CIVIL RELIGION

Sociologist Robert N. Bellah defined civil religion as “that religious dimension, found I think in the life of every people, through which it interprets its historical experience in the light of transcendent reality.”[1] In a groundbreaking 1967 article he described how, beyond ideas of America as a Christian nation, “there actually exists alongside of and rather clearly differentiated from the churches an elaborate and well-institutionalized civil religion in America…. But the civil religion was not, in the minds of Franklin, Washington, Jefferson, or other leaders, with the exception of a few radicals like Tom Paine, ever felt to be a substitute for Christianity. There was an implicit but quite clear division of function between the civil religion and Christianity.”[2]

Dulles’ boss President Dwight D. Eisenhower put it in broad terms, marking a qualified confusion of the two spheres described by Bellah, and helping to explain Eisenhower’s promotion of the newly melded “Judeo-Christian” model:

…this is how they [the Founding Fathers] explained those [civil religious beliefs]: “we hold that all men are endowed by their Creator…” not by the accident of their birth, not by the color of their skins or by anything else, but “all men are endowed by their Creator”. In other words, our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is. Of course, it is the Judeo-Christian concept, but it must be a religion with all men being created equal.[3]

Bellah argued that such civil religion can involve myths of origin, national exceptionalism, and a sense of defining a people in relation to others, often by contrast and even conflict. However, it also served in his view as a basis for the very survival of a society, by providing unity of spirit. He wrote of how civil religion as a product of mid-20th-century American liberal Protestantism likely encouraged ecumenical (and hence ultimately globalist) traditions of civility, tolerance and open-mindedness. Even so, Bellah’s implicit embrace of civil religion, adopting a term from Rousseau and the French Enlightenment, itself was implicitly secularist and modernist in its attention to “myth.” Bellah’s own fondness for the concept, as the leading 20th-century American scholar on the issue, was by his own admission related to his own background in Mainline Protestantism, identified with American civil religion in the Eisenhower-Dulles period, which scholarship since has described as a kind of fourth “Great Awakening” in American religious history (on the count of which, see further below).

The Eisenhower-Dulles era arguably saw a distinctive departure from Bellah’s basic definition, namely the merger of civil religion with elite ideas of Christianity as a philosophy (rather than a traditional but living faith), blurring lines of distinction between that and civil religion, and providing an opportunity for those who were non-religious or from non-Christian backgrounds to minimize the direct role of Christianity in American national culture. At the same time, the heyday of Mainline American Protestantism in the Cold War saw its liberal activist and Deistic tendencies give rise to a distinctive universalist exceptionalism. about American idealism, which justified a type of cultural neocolonialism in the new global West. The particulars of this evolving American view became projected as universal culture and progress for the world. Sympathizers like Bellah reasonably might emphasize that this “revival” of civil religion in the 1950s contributed to a sense of unity in the American-led fight against global Communism, providing a basis for example for the U.S. Civil Rights movement under the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

But turning Christianity into more of a generic national philosophy of “Judeo-Christian values” arguably also contributed to dissolution of any traditional fabric for elite American life, however frayed, as well as setting up later generations for extremist utopianist views on a broader scale essentially hostile to traditional Christianity. Christian liberalism morphed across a few generations among American elites into essentially non-theistic and Unitarian-leaning outlooks. Heavily inflected by faith in social reform and technological progress, that theological orientation melded with civil religion. Hieromonk Seraphim Rose in the 1970s viewed the trend from the other end of the turbulent 1960s, as evolving then into a New Age spectrum of post-Christian spirituality. He saw this as a trajectory from his Orthodox Christian perspective as moving to a non-theistic or “super-theistic” (far outside of Orthodoxy) inclusion of the occult and the perverse, on a broader scale than ever before in American culture at large. In fact, he admitted how in reaction to what he felt was the shallowness of American Mainline Protestantism in the 1950s he himself fell prey to nihilism while coming of age in southern California. He turned at first for meaning to Chinese philosophy alongside his dissipated lifestyle, before converting to Orthodoxy under the influence of the prominent modern Orthodox Saint John (Maximovich) of Shanghai and San Francisco, and becoming a monastic.

Movements influenced by non-Christian religions and intellectual currents worldwide, such as Deism, New Thought, Theosophy, Freemasonry, Spiritualism, Marxism, Utilitarianism, and Darwinist Scientism, as well as a developing techno-pantheistic outlook in the sexual revolution, had for generations been playing an increasing role in American life, even before the era of the Cold War “Great Awakening” of civil religion in America in the 1950s. But the unified turning of establishment American Protestantism further away from many basic traditional Christian beliefs and practices, enfolded into the Cold War civil religion, arguably laid a key foundation to Hieromonk Seraphim’s history of a “religion of the future” at odds with Orthodoxy.

Developments in Dulles’ era had precedence in the morphing of New England Puritanism into old-school Unitarianism in the late-18th and early-19th centuries. There was an analogy, from an Eastern Orthodox perspective, to the developing creed of rationalistic-yet-romantic civic religion earlier in revolutionary France. That “civic religion” (an officially established civil religious culture) was critiqued in Orthodox terms by the “Kollyvades” writer St. Athanasios Parios in his 1798 apologetic book An Apology for Christianity. Anthony Ladas, in introducing his new English translation, notes how “the supremacy of the secular civic religion” emerging from the French Revolution, despite bows to religious tolerance, involved “the proverbial ‘pinch of incense to Caesar.’” It demanded that sects be in accord with the revolutionary republican project, and its violent dis-establishment of Catholicism, while literally enthroning secular reason as a new civic religious focus. “Anything less was [labeled] fanaticism,” Ladas wrote in glossing St. Athanasios’ critique. “In a way then,” Ladas concludes, “the Enlightenment in France did not simply revive pagan philosophy, but also the marriage of pagan religion and politics…. [to] tolerate all cults that submitted to the genius of the state.”[4] The civic religion described in post-revolutionary France however separated itself clearly from Christianity, unlike the American-Dulles version.

Despite the sharp contrast between revolutionary France and Cold War America (in which any alleged parallel of Robespierre and Eisenhower would seem comic!), 1950s America did see a rise in the influence and status of secular science in education, under the banners of neo-Darwinism and technological progress. The rise in popular Cold War piety ironically saw a decreasing presence for traditional Christianity in education, featuring what C.S. Lewis called “scientism,” while legal cases restricted prayer, Bible reading, and ultimately “Creationism” in public education.[5] The nationalism of the American renewal beginning in World War II effected extreme reverence for the American flag; the “flag code” (enacted as federal law in 1942) made it a sacred object in effect, part of a type of national cult with minimized traditional religious associations. So far as American educational and media culture went, Neo-Darwinist evolutionary views in the 1950s, with an accelerating sexual revolution, proved more decisive socially than the symbolism of Eisenhower’s well-publicized baptism as a Presbyterian during his first term. Technological advances became venerated more than Christian faith in popular culture. For example, at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, when Walt Disney’s General Electric-sponsored Carousel of Progress made its debut (later an attraction at his theme parks), its celebration of technological progress and total neglect of faith (seen in a 2023 video in an updated version) ironically seemed a nihlistic capitalist-consumerist mirror of Communist atheism.

In an Orthodox view of the theological basis for these trends in the long term, the Priest-Martyr Daniel Sysoev attributed heretical tendencies of Protestantism to the ancient heresy of the Monophysites.[6] Sysoev’s analysis may seem counter-intuitive at first, given the emphasis in Protestant practice often on Jesus Christ which can seem non-Monophysite, and obvious differences between Protestantism and historical Monophysite sects in the Near East. However, from a deep-structural standpoint, Monophysite tendencies in Protestantism make sense as derivative of the filioque, and how it affected Western theology across centuries.

The adoption of the filioque in the Western revision of the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed shaped a more binary view of the Trinity. Asserting that the Holy Spirit “proceeds from the Father and the Son,” rather than just from the Father as did the Creed earlier approved by Ecumenical Councils, the revision emphasized an originate meld of the Father and of the Son in the Trinity, which downgraded in effect the Holy Spirit. It added to Western Trinitarian emphasis on the “One Essence” at the expense of the “Three Persons.” This also encouraged Scholastic views of the grace of God as created. Overall, such developments aligned with a more rationalistic and individualistic approach in Western culture, which ignored the key Orthodox Christian teaching of the uncreated nature of grace or energies of God. It fostered a lop-sided heretical sense of the Trinity together with a more “rationalistic” view of individualized grace, which helped enable the rise of Unitarianism and Deism in American Protestantism. As the “Great Awakening” of civil religion in the 1950s arguably reached for a lowest-common-denominator of Protestantism to rally against Communism, from an Orthodox standpoint it unwittingly tapped further into that cultural tendency toward heresy, helping to enable a generic sense of religion in Unitarian or Deistic terms. This arguably helped make American culture at least at the elite level more susceptible to pantheistic developments of the New Age religion critiqued by Hieromonk Seraphim. American-led ecumenism (under the auspices of initiatives such as the World Council of Churches, aligned with the American National Council of Churches whose growth Dulles assisted), continued to become more global in outlook while arguably wandering further from traditional Christian roots.

The underlying Monophysite theological analysis of the ultimate background of the 1950s civil-religion “awakening” is not exclusive from an Orthodox understanding. It also needs to take into account that many Protestant denominations overtly remained allegiant to Chalcedonian Christanity on the level of doctrine, and not all were highly individualistic in structure. However, from an Orthodox perspective, an underlying Monophysite sensibility or culture can be discerned in combination with heretical emphases related to the filioque and created grace, all involving an emphasis on individualism and rationality, the latter exacerbated across denominations by the melding of Mainline Protestantism with civil religion. All these factors arguably relate, from the standpoint of Orthodox ecclesiology, to the fracturing of Mainline Protestantism from the apostolic universal Church in its organic and historical form as the Orthodox Church, to a current state of an estimated 45,000 Christian denominations in the world, many represented in the U.S. In other words, although some core Mainline Protestant ecclesiastical organizations such as Lutheran and Episcopal uphold forms of bishops and claim apostolic connections, they are not part of the Orthodox Church as a whole, and often tend to accept the “invisible Church” ecclesiology common to Protestantism, by which there can be many branches and organizational networks of the Church in separate hierarchies and governance entities, aspirationally united in an ecumenism. Orthodoxy rejects that doctrinally based on her sense of the historical and embodied Church as founded by Jesus Christ, as the Body of Christ.

THE AMERICAN CIVIL RELIGION AWAKENING

University of Virginia historian William I. Hitchcock, author of The Age of Eisenhower: America and the World in the 1950s (2018), has noted the “great awakening” of American civil religion saw church membership rise from 49 percent of Americans in 1940 to 69 percent in 1960 (religious historians often categorize three or four Protestant “evangelical” Great Awakenings in US history, not including this distinctive wave–the first two were in early American history, the third in the late 19th- and early-20th century including both Social Gospel and evangelical revival coupled with the rise of the YMCA movement and Prohibition). During World War II many families returned to worship services for family members in the military abroad. Servicemen carried with them pocket New Testaments issued by the government with a message encouraging their piety from President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Hitchcock notes how during the 1950s, besides Eisenhower and Dulles in government, iconic religious figures emerged in American public media encouraging the new civic piety of the Cold War era, especially the Mainline Protestant Rev. Norman Vincent Peale (trans-denominationally serving as a Methodist and Reformed Church of America minister), the Catholic Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, and the Evangelical Billy Graham.[7]

(Above) Rev. Norman Vincent Peale, the Mainline Protestant apostle of “positive thinking” in the American 1950s, and pastor to Pres. Donald Trump’s family–with Billy Graham and Cardinal Fulton Sheen one of the icons of the new civil religious revival.

But the weakening of traditional Incarnational theology in the Mainline American Protestant “Seven Sisters” also accelerated in Dulles’ era.[8] Throughout the twentieth century, the emerging elite sensibility of religion in Dulles’ older generation of White Anglo-Saxon Protestantism in the U.S. (he was born in 1888) centered increasingly on a vague Deism. Compatible with postwar individualism and consumerism, it melded old-style Progressivism and Social Gospel traits of Dulles’ faith background with Cold War globalism and notions of American exceptionalism.[9] All of this is not surprising when considered through the lens of two classic studies of American culture relevant to the fate of establishment U.S. religion: 1. Sociologist Max Weber’s work on capitalism in Protestant countries outlined the great appeal of material success in Calvinist theology.[10] That underlined who might be considered among the ranks of the elect. This contributed in the long run to a drive to secular conformity, too, boosted in Dulles’ era by postwar American prosperity and the rising demographics of the “baby boom” alongside use of mass media. 2. Alexis de Tocqueville’s earlier critique of American democracy had included warnings about the potential negative influence of the tendency toward conformity and mob rule in American life.[11] Such foundational cultural attitudes boded ill for traditional Christian beliefs and communities when they encountered extreme prosperity, consumerism, and mass media in the post-World War II era, and helped enable the weaponizing in effect of generic Christian public rhetoric as civil religion during the Cold War.

Serving at the highest level of the U.S. government, Dulles publicly supported President Eisenhower’s cause of “Judeo-Christian values” as key to the struggle with the Soviet Union and its allies such as (through most of the 1950s) Communist China. Under the Eisenhower administration that featured Dulles as a key leader, “In God we trust” became the national motto in 1954, placed soon over the dais of the U.S. House of Representatives (as the Evangelical Speaker Mike Johnson retrospectively observed in his inaugural 2023 address), and emblazoned on paper currency as well as coinage. “One nation under God,” a phrase from Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, was added to the U.S. Pledge of Allegiance. In 1953, Eisenhower became the first and only President baptized a Christian while in office, at the D.C. National Presbyterian congregation where Dulles and his wife were affiliate members. He instituted prayers at Cabinet meetings and supported national prayer days. At the same time, Eisenhower also was famous for his above-mentioned statement about this “Judeo-Christian” civil religion that “I don’t care what it is. Of course, it is the Judeo-Christian concept, but it must be a religion with all men being created equal.” He also laid the cornerstone for a new headquarters for the National Council of Churches in New York City in whose origins Dulles had been active, and which at the time was receiving funds from a CIA front organization, the Foundation for Youth and Student Affairs, to support its perceived strengthening of anti-communist “Judeo-Christian values.”[12]

Dulles’ less-religious brother Allen in fact was in charge of the CIA in the Eisenhower administration. The U.S. provided support for the Orthodox Christian Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul to help shore up Greek anti-communism in the post-World War II era (flying the newly elected Patriarch of Constantinople, Athenagoras, to Turkey from America in 1948 for his investiture). America in this period also aided the emergence of the state of Israel as a Jewish state, further buttressing “Judeo-Christian values” globally as the U.S. became directly involved in the Middle East through the 1957 Eisenhower Doctrine. Meanwhile, focused on East and South Asia, the anticommunist “China Lobby” in the U.S. grew from elements of Catholic and Protestant Christian missionary networks displaced by the Communist takeover, bearing in mind that the two pre-Communist nationalist Chinese leaders, Sun Yat-Sen and Chiang Kai-Shek, had been Protestant Christians in a missionary culture deeply influenced by Mainline U.S. Protestantism.

One micro-example of the effects of all this on the ground can be seen at Bucknell University, originally a Baptist university in the Northeastern United States when founded in 1846. Bucknell built a new chapel in the early 1960s. Eschewing a Cross on the steeple, it featured a metal grillwork at the front of the interior worship space highlighting Jesus and Moses equally, illustrating Eisenhower’s equation of Jewish and Christian traditions, alongside symbols of a variety of biblically related faiths ecumenically, with Unitarian-Deist overtones. During the 1950s, the last vestiges of the university’s official Protestant denominational connections had been removed, with the end of requirements that a few key officials still be members of that tradition. One prominent cross-generational family associated with the university during the post-World War II era spanned roles from Baptist mission work in Asia in the first generation, CIA work in the next, and then in the third generation a non-believing family member who was a liberal activist professor at the school, a trajectory exemplifying changing phases of the “Great Awakening” of American civil-religion.

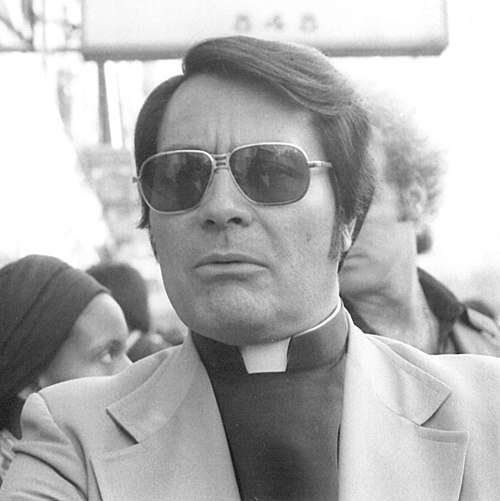

In the brief sections that follow, the Cold War civil religion exemplified by Dulles will be used as an example of the further devolving of American elite Protestantism into a de facto culture of Monophysitism (again, a denigration of the Trinity and the historic Church by the increasing denial of traditional aspects of Jesus’ Incarnation) in globalization following World War II. His example then will be paralleled with the role in this same complex process of the American-born elite denomination of Christian Science, as an heretical Anglo-American Unitarian sect with unusual access and influence on the transition of Trans-Atlantic power from British to American empires, and in American politics and national security agencies, during the Cold War. Finally, a spectacularly evil “next generation” case will be considered in Jim Jones, a pastor with his community in the Disciples of Christ denomination, alongside Dulles’ Presbyterian Church USA one of the “Seven Sisters” of mainline American Protestantism. Jones and his community remained affiliated with that liberal mainline denomination (also ironically the childhood religious affiliation of President Ronald Reagan) until its end in mass suicide and murder. Jones’ globally oriented religion based in Northern California (ending in Guyana while leaving cult property to the Soviet government in its legal “will”) became the most famous illustration of revolutionary spiritual nihilism unleashed in the next generation after the emergence of postwar American civil religion. An exact cause-and-effect relationship is of course lacking, but the loosing of Mainline Protestant theological requirements in the era of Dulles’ youth, coupled with the move to meld Protestantism with social concerns during the Cold War, helped shape the political and civic culture in which Jones later would perversely thrive for a time. A concluding reflection will be offered from Orthodox Christian perspectives on the Monophysite elements of globalist spirituality as it developed from establishment American Protestantism, and on the entwined threads of liberal and conservative globalization in above-mentioned three examples.

AMERICAN CIVIL RELIGION AS NURTURER OF SECULAR GLOBALIZATION

“In God we trust,” made the national motto in 1957, was added to all U.S. currency (the new global exchange currency) under efforts by President Eisenhower and Secretary Dulles to mobilize “Judeo-Christian values” as a new U.S. civil religion to combat atheistic Communism. At the same time, symbolism on the dollar bill echoed Deistic Masonic symbolism.

Dulles, through his pastor father and his own reading and role as an attorney involved in denominational conflicts, was very influenced by the Protestant Social Gospel movement in America, which also centrally informed the Great Awakening of 1950s American civil religion. As John D. Wilsey described the foundational progressive Protestantism of the 20th century in his spiritual-political biography of Dulles:

Progressive Christianity, while it predominated between the Civil War and World War I in America, remained a significant cultural and intellectual force at the beginning of the Cold War. It was forged by figures like Washington Gladden, pastor of the First Congregational Church of Columbus, Ohio; Walter Rauschenbusch, author of A Theology for the Social Gospel; Frances Willard, president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union; Shailer Mathews of the University of Chicago; William Newton Clark of Colgate Theological Seminary; William Adams Brown of Union Seminary; and Harry Emerson Fosdick of Riverside Church in Manhattan, among many others. Theologically liberal, progressive Christians chafed against confessions of faith, emphasis on doctrine, and religious authority based in Scripture, tradition, or the institutional church. Progressive Christianity was modernist, and as an intellectual system influenced by evolutionary theory, it prevailed over fundamentalism by the 1920s. Foster [whom Dulles had defended as an ecclesiastical attorney in his early career] was at the center of both the civil religious awakening of the 1940s and ‘50s and the progressive Protestant movement of the interwar period, both shaping and being shaped by these religious dynamics.[13]

Interestingly, the evangelical movement and the rise of the so-called “Christian Right” in the later 20th century represent, from an Orthodox Christian standpoint, something of a “flip side” to the progressive Protestantism described above. Both contributed to and derived from American civic religion as it developed across the 20th century. The nature of that civic religion became contested. But for the conservative wing it involved recognition of America as an exceptionalist Christian nation, with efforts to renew that in the civic realm in ways including moral legislation and education, as well as subscribing to Christian Zionism. Inwardly, right-wing evangelicalism that contributed to the 1980s “Reagan coalition” had its own way of eschewing both traditional creeds and emphasis on doctrine, along with religious authority based in Scripture, tradition, and the historic church. Superseding in effect “religious authority based in Scripture,” both progressive and right-wing American Christianity during the 20th century involved rejection of tradition and the institutional church as understood in Orthodoxy. In effect, from an Orthodox standpoint religious authority based in Scripture was made subservient to interpretation by prominent preachers in sermons central to many modern Protestant services and derivative writings and broadcasts, as well as to individual interpretation by each reader-believer in an almost postmodern sense of a subjective fundamentalism. (Indeed the resurgence of evangelicalism in the “Reagan era” has been called by some scholars another “Great Awakening”–in the schema followed in this article, it would be the fifth after the rise of civil religion in the 1940s and 1950s, succeeded by a sixth in the 2010s and 2020s, the so-called “Great Awokening” of religious-style progressive ideology leaning into the “post-Christian” more overtly.)

The early formative influence of progressive Protestantism on American civil religion can be symbolized also by the early influence and ubiquitous presence of offshoots such as the Boy Scouts of America (related to Masonic ideas of Deistic ecumenism) and the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). The fact that the 2024 re-election campaign of Donald Trump, a spiritual son of Rev. Norman Vincent Peale, used the pop-culture song YMCA as its theme was an odd indicator of the meld of conservative and liberal in U.S. civil religion by the 2020s, for the song originally was a kind of homosexual anthem, yet was being danced to on national media not only by the candidate but by many of his evangelical Christian supporters, as well as a notable contingent of LGBTQ supporters who took leadership positions in the second Trump administration.

The combining of a Deistic-leaning civil religion with ideas of American exceptionalism had deep roots in U.S. heterodox theology. For example, the early English émigré to America Joseph Priestley advocated for a Unitarianism combining his own version of literal application of Biblical prophecy with a deterministic view of history, a mix easily adaptable to American exceptionalism. A significant difference between Orthodox views of the role of the Church and that of American civil religion involved the former’s deep Trinitarianism (not accepting the filioque) and related mystical ecclesiology of the Church as above and beyond the state. In Orthodox symbolism of the double-headed eagle, the Church and the State while spiritually united had distinct “heads,” and could act as checks and balances on one another. There were only weakened parallels to Orthodox ecclesiology in fragmented American Protestantism, whose historical formation lay vaguely in state religions of the Protestant monarchies of Europe. Charges of Caesaro-Papism against Russian Orthodoxy by Protestants ironically find their basis in elements of Church governance adopted from Protestant state denominations by Tsar Peter the Great in Russia for a time.

It was appropriate that Dulles personified the civil religion “Great Awakening” of the Cold War given his earlier prominence in the precursor to the Presbyterian Church (USA). That denomination’s roots went back to the founding of America. Indeed, the involvement of its ancestor sect in many missionary and social projects, as what became known in the Civil War era as “the northern Presybyterian church,” and its relation to earlier American Protestant “awakenings,” made critics of other religious backgrounds fear that it would become in the 19th century a kind of state Church. That never happened officially. But the type of progressive Protestantism in which the Dulles family was rooted in liberal Prebyterianism became culturally the basis for evolving cross-denominational global American religious reach in the 20th century. American civil religion as it arose especially in the 1950s with Dulles as a representative has been characterized as featuring both qualified belief in progress, and American exceptionalism, with an element of Cold War Manichaeism, in terms of a duality of good versus evil, thrown in for good measure.[14]

To sum up, the civil religion of Dulles, with its many elements and branches, involved a Deist-leaning theology that, like Monophysitism, tended to emphasize the divinity of Christ at the expense of the historicity of the Orthodox Church and her traditions. Its resulting Manichaean elements shadowed a gnostic sensibility of the spiritual or conceptual (arraigned ultimately in technocratic terms) as reality, and matter as unreal and instrumental. Writers such as Eric Voegelin and James Burnham in the twentieth century saw such cultural trends as leading toward a technocratic, management state with experts as its elite. This worldview, related historically to American exceptionalism, encouraged a globalistic secular viewpoint, informed by dominant American technology and multinational corporate development, and organizations such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and United Nations and World Bank. Aspects of utopianism in the worldview of American civil religion fed both social justice and neoconservative movements, the latter emphasizing the need (in Dulles’ view) for an American-regulated world order. Neo-conservatism included leading theorists and advocates of Jewish background, buttressing the Eisenhower administration’s emphasis on “Judeo-Christian values.”

In terms of Anglo-American globalism in the interwar years, Wilsey’s biography notes Dulles’ close relationship with the English globalist Lionel Curtis, a member of the England-based Milner Group, and with the founding of the Council on Foreign Relations, which the Milner Group originated. The globalist and liberal influence of that Anglo-American network aligned well with the general worldview of Dulles and American civic religion as it developed, reflecting the original influence of John Ruskin’s non-Orthodox but communitarian outlook on its founders. The “Milner Group” as a term popularized by Georgetown historian Carroll Quigley described a loose British-based network of influencers, successors of Cecil Rhodes’ imperialist circle, who founded and in effect operated entities such as the Royal Institute of International Affairs (better known as Chatham House), its offshoot the Council on Foreign Relations, with significant influence also on All Souls College at Oxford and The London Times. Some of the members of the Milner Group had been in the so-called “Milner Kindergarten” as young men, with its leader Alfred Milner having been mentored by Rhodes. Generally, the outlook of the Milner Group, including Dulles’ alley Lionel Curtis, encouraged continuation of ideals of the British Empire in some form of world federalism, particularly the Commonwealth of Nations, but also other entities including the League of Nations. Curtis and Dulles shared involvement in the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, from which the League of Nations (a predecessor to the United Nations), and the Royal Institute of International Affairs and the Council on Foreign Relations emerged. Significantly, Quigley in his study The Anglo-American Establishment described the heretical sect of Christian Science, examined further in the next section, a significant element in the development of later American civil religion, as the informal religion of the Milner Group from the 1920s into World War II.[15]

Above: Walt Disney with figures from “It’s a Small World.”

Contemporary to Dulles, the American entertainment magus Walt Disney reflected this new establishment spirituality in popular culture. Disney, from his own affinity for civil-religion Protestantism and with a family influenced by Christian Science, became for a time arguably the global bard of what Rose’s book called “religion of the future” in its early stages. The movement became encapsulated in the trajectory of his “It’s a Small World” techno-performance exhibition at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Related to Disney’s earlier involvement in Eisenhower’s “People to People” program, it was meant to be a tribute to the United Nations’ efforts for children in need worldwide (UNICEF), sponsored by the Pepsi-Cola company. Moved to Disneyland afterward in a ceremonial opening featuring “real” children of the world dressed in a variety of folk garb, the popular attraction was featured too on television and in musical recordings. It illustrated the arrival in popular culture of the new ecumenist spirituality of Cold War globalism, and complemented the corporate-sponsored “Carousel of Progress” already mentioned. At Disneyland, it joined among popular attractions the nostalgic Main Street USA, which despite mimicking a traditional American community, notably had no houses of worship (and neither did the “It’s a Small World” and “Progress” attractions bear any mention of Christian or other faith).

CHRISTIAN SCIENCE AND GLOBAL SPIRITUALITY’S EMERGENCE FROM AMERICA

Next we turn briefly to Christian Science, a spirituality involving Disney’s family, for a more primordial (if you will) example of American civil religion as the “religion of the future” in Hieromonk Seraphim’s meaning, with origins in the late 19th century. Christian Science like Disney had a notable if less popular presence at the New York’s World Fair of 1964, with a futuristic structure as a Christian Science Reading Room, later moved to California to be a church building, and its own identifications with Cold War globalism.

On the left above, Christian Scientist Lord Lothian (Philip Kerr, British Ambassador to the U.S.) was part of a network of influential Anglo elites in the early 20th century associated with the so-called Milner Group, a direct descendant of Cecil Rhodes’ circle. Georgetown historian Caroll Quigley described Christian Science as the informal religion of the Milner Group. On the right side of the photo are two other Christian Scientists in that social network, Lord Waldorf and Lady Nancy Astor.

The sect together with Mormonism was long touted as one of the two great American-born religions, although more urban and Trans-Atlantic in its Anglo-Americanism than the Latter Day Saints, as indicated by the elite success of its main publication, The Christian Science Monitor. It had emerged during what some scholars have called the third Great Awakening of Protestant America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, separate from but alongside the Social Gospel movement with a distinctively global un-orthodoxy. A healing cult entangled with British Israel beliefs in Anglos as God’s chosen people, its heyday paralleled the floruit of John Foster Dulles, with its sharp decline and virtual disappearance coming a generation or two after his 1959 death. Yet few Protestant American sects afford such a glimpse into the nature of American civil religion and its contribution to a post-Christian Global West. In many ways it pioneered the civil-religion awakening of the 1950s that Dulles helped lead. As mentioned, it was described as informal religion of the Milner Group of British imperial elites, due to the influence of Christian Scientists Lord Lothian and Lady Astor, in the era after World War I when the British Empire was at its high-water mark territorially, but in decline economically and socially, looking to the more vibrant and wealthy United States for a translatio imperii between White Anglo-Saxon elites of the day.

In Boston’s Back Bay district lies the distinctive campus of buildings that since the late 19th century has been headquarters to the Christian Science denomination. The structures range in architecture from a Romanesque-style stone temple to an immense domed edifice with Byzantine echoes, to other buildings reflecting 1960s brutalist architecture. Walking into the 1934 Christian Science Publishing Society building, headquarters of The Christian Science Monitor newspaper and now also the Mary Baker Eddy Library (named for the denomination’s founder), one enters the glass orb of the Mapparium. It is a unique sphere from which the visitor stands inside a world globe in which the boundaries of the British Empire stand oddly frozen near the time of its territorial height.

The “Mapparium” (above) at the Christian Science Center in Boston is a three-storey glass sphere that preserves world boundaries from 1935 in the British Empire’s lingering heyday. The Christian Science Monitor newspaper headquartered in the same building became an important voice for early Anglo-American globalism, and Christian Scientists enjoyed prominent roles in U.S. service during the Cold War.

The Byzantine-looking dome of the main worship structure on the campus is a reminder of how Christian Science presented itself as going beyond establishment American religious organizations to a more authentic faith when Orthodoxy was still virtually unknown to Anglo-American elites. But, in the process, its extreme Unitarian and Universalistic theology and healing practice, in their spiritualization of matter, became a system that culturally helped to enable early globalization fostered by Anglo-Saxon Trans-Atlantic links in the mid-20th century.

The eclectic architecture of the Christian Science Center (above, photo by LAM Partners) reflected the sect’s effort to assert a global role.

At the time of the opening of the Christian Science Mapparium globe in 1935, the cult of Christian Science was, according to Quigley also an important element of the aforementioned Milner Group, an elite English social network and successor to Cecil Rhodes’ original liberal vision for imperialism. Quigley described the focus of the Milner Group as working to advance a type of world federalism through the Commonwealth of Nations and affiliates. Reaching an apparent numerical peak from the 1920s through the 1950s, Christian Science’s momentum among elite Anglo-Americans continued into the 1970s with an out-sized presence of adherents in influential positions in the Nixon White House. It had members heading the U.S. FBI and CIA in the latter part of the 20th century, as well as a disproportionate presence in the U.S. Congress, and prominence in mid-20th century classic Hollywood. The writer Tom Wolfe in his The Right Stuff identified Christian Science as more elite than even Episcopalianism in the U.S. Navy and space program of the early Cold War.[16] John Gunther in Inside U.S.A. described a powerful cluster of upscale Christian Scientists in Manhattan during the same period.[17] Corporate leaders of such post-World War II old-line businesses as the Whirlpool Corporation and Bell & Howell were Christian Scientists, and even as late as the 1990s and early 2000s the Christian Scientist Henry Paulson headed the Wall Street financial giant Goldman Sachs and then the U.S. Treasury Department under the second President Bush.

As an indication of the cult’s standing in popular culture during Dulles’ day, Robert Heinlein’s famous 1961 science-fiction novel Stranger in a Strange Land foresaw only Catholicism and Christian Science resisting (albeit fruitlessly) the new extraterrestrial spirituality seizing America and the world. In this, Christian Science served as a symbol in effect for derivative White Anglo-Saxon American Protestant religious culture with roots in Puritan New England’s “city on a hill.” This was the view projected by Christian Scientists in the 1950s, offering it as an enlightened and establishment Unitarianism allied with the “positive thinking” culture increasingly celebrated in mainstream U.S. Protestantism. The already mentioned guru of the latter movement, Rev. Norman Vincent Peale, would lead the informal magisterium of Protestant clerics who met with and examined presidential candidate John F. Kennedy in 1960, as to whether Kennedy would be free of papal influence if serving as the first Catholic president of the U.S. Peale also would be pastor to young Donald Trump, whose estate Mar-a-Lago coincidentally was built earlier by a Christian Scientist, the cereal heiress Marjorie Meriwether Post.

But in American popular culture during the immediate post-World War II era, perhaps no figure was more central than Walt Disney. Disney’s wife and daughters reportedly were involved with Christian Science. He is said to have commented positively on it. Certainly, his incredibly influential “once upon a dream” and “when you wish upon a star” visions of following your will for success and happiness (whether in movies, animation, television, theme parks, merchandise, or music) fit well with the culture of Christian Science and positive Protestantism in the 1950s, as seen also in the aforementioned “It’s a Small World” promotion of globalization.

The Christian Scientist H.R. Haldeman ran the Disney account for a prominent advertising agency and was even rumored as a potential successor to Disney himself (in 1967 he was made Chairman of the Board of the California Institute of the Arts founded by Disney and his brother Roy). But Haldeman hitched his career to the star of political candidate Richard M. Nixon, like him and Disney a prominent southern Californian with Christian Science connections, a region where the religion’s culture was especially pronounced in areas such as Orange County and Los Angeles/Hollywood. Haldeman jumped from Nixon’s election campaigns in the 1960s to became Nixon’s White House Chief of Staff when the latter took office as President in 1969. With another West Coast Christian Scientist, John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s chief domestic policy advisor, and other adherents, Haldeman formed part of a significant Christian Science clique in the administration of Nixon, whose mother-in-law had been a Christian Scientist and whose wife had been partly raised in the faith. The interfaith ecumenical services at the White House instituted by the Nixon administration reflected Christian Science sensibilities in a general way as well. Later, former Nixon aide Chuck Colson, who himself was briefly interested in the faith, argued that the influence of Christian Science partly explained the Watergate scandal, citing the doctrine’s belief in the unreality of evil as contributing to a lack of discernment. He connected this blind spot of positive thinking also to earlier alleged appeasement tendencies of the Christian Science-influenced Cliveden Set of the Milner Group in England during the 1930s.

The surfacing of Christian Science in the public realm in the Nixon administration reflected a deeper history of the heresy’s relation to beliefs in Anglo-American exceptionalism. Mary Baker Eddy, its founder, in the 19th century, liked to cite her Puritan ancestry and growing up in the derivative Congregationalist faith. Christian Scientists did not celebrate Christmas or Easter in any special way, but did have a special service each year for the American national holiday of Thanksgiving, rooted in the New England Pilgrim-Puritan tradition. Many of its believers including Eddy adhered to versions of the “Anglo-Israel” ideas that the Pilgrims and English generally were part of a lost tribe of Old Testament Israel. Also, part of the appeal of Christian Science in its heyday was a perceived Stoicism and rigorous self-discipline in its approach to suffering, with more of a biblical basis (if a false one from any Orthodox standpoint) than many more generic forms of positive-thinking and New Thought and nascent New Age or occult approaches at the time.

In American religious history, Christian Science’s gnostic denial of matter and advancement of an “impersonal” Christ, upholding spiritual healing and a sense of apocalyptic mission (identifying its denomination with the Holy Spirit), marked the sect as a bridge between fragmenting American ecumenist Protestantism and the New Thought and New Age movements, paralleling the growth also of non-Christian Asian religious influence in America, such as the Theosophy movement. Its focus on healing both denied matter in New Thought terms, and spiritualized it in ways recognizable to New Age movements. Eddy, its founder, liked to cite her personal and family connections with New England Congregationalism as descended from Puritanism, and Freemasonry and American Transcendentalism. But her biographies also show her connections with the origins of New Thought that became ancestor to the “Positive Thinking” and “Prosperity Gospel” movements (both influential on current U.S. President Donald Trump).

The denomination’s newspaper, The Christian Science Monitor, for decades provided a media outlet for voices from the loose cultural network of the Milner Group and its affiliated Royal Institute of International Affairs (Chatham House) and its spinoff the U.S. Council on Foreign Relations, with related groups across the British Commonwealth, including the later Trilateral Commission. The memoir of acclaimed Christian Science Monitor journalist and television commentator Joseph C. Harsch details his extraordinary journalistic access to Anglo-American elites in the Transatlantic alliance during World War II and after, reflecting the elite reputation of the sect’s daily publication.[18]

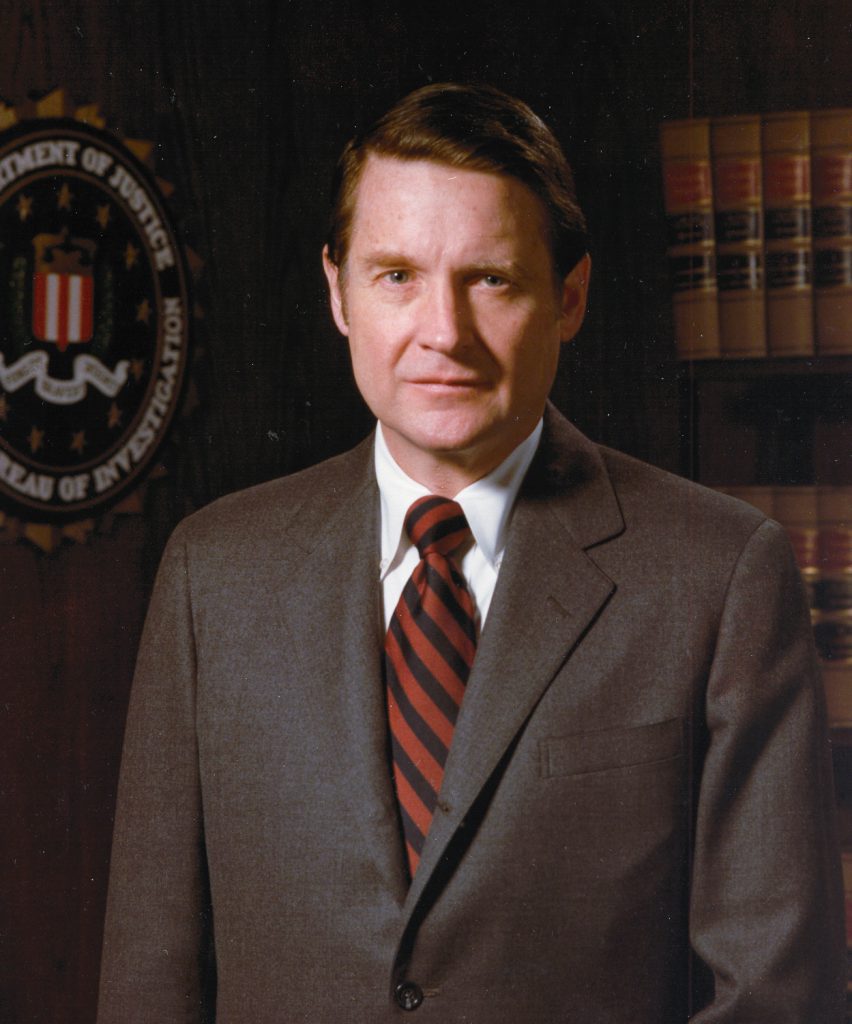

Judge William Webster, the only person to head both the FBI and CIA, was a Christian Scientist, and good friend of former CIA director Admiral Stansfield Turner, also a Christian Scientist.

The cult since has dwindled almost to extinction in the 21st century, challenged by diminution of old-school White Anglo-Saxon Protestant racialist identity among elites, advances in medicine that exposed the flaws of its therapy, and the denomination’s own internal ossification. But its well-defined history and ongoing indirect influence remain interwoven with the rise of a global civil-religious culture from America, which came to emphasize individual willpower, positive thinking, and a technologically allied emphasis on the spiritualization of matter and plasticity of the natural environment. A new generation of such thinking exists today in various Silcon Valley-related transhumanist techno-cults and philosophies.

Writer Carolyn Fraser, a former Christian Scientist, in a memoir-history of the movement, has called Christian Science chameleon-like in how it blended into American mainstream culture while a cult concealing a record of deaths of children and others due to lack of medical care.[19] In fact, the Nixon administration provided special legal exemptions for medical care for the faith through federal regulations, as well as a special copyright extension for the Christian Science text. Both were repealed later, but showed the sect’s influence. Former U.S. Senator and Christian Scientist Charles Percy, Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee during the Reagan administration and previously head of Bell & Howell, praised his denomination as well-managed in a business-like way. Indeed, the leaders of the denomination are styled “the Board of Directors” in corporate-like terms; there are no traditional clergy and hierarchs. In addition, Christian Science is governed by a “Manual” written by Eddy, a text with gaps and apparent contradictions, studied by Christian Scientists a bit like jurists might study the U.S. Constitution.

In accord with the Manual, the denomination does not disclose membership statistics. But U.S. Census date from the 1930s indicated at that time about 250,000 members in the U.S., equaling some estimates for the number of Orthodox Christians in the U.S. in the early 21st century. That number may have increased a bit after that, but by 2025 likely has reached as low as 20,000 or so, at least in terms of denominational membership. The reach of those influenced by Christian Science through its publications and affinities in New Thought and “positive thinking” circles, however, was larger if immeasurable. Its elite presence and influence continued to be disproportionate to its numbers, despite controversy over its reliance on prayer rather than medicine for healing, which from an Orthodox standpoint involved heresy relying on alleged miracles that were delusional and detrimental to Christian spiritual life.

Historian Quigley wrote of its presence in the social network succeeding the circle of arch-imperialist visionary Cecil Rhodes, amid a key group of “influencers” in waning imperial Britain. Quigley (himself a professorial mentor to U.S. President Bill Clinton, a Rhodes Scholar himself) argued that “there grew up in the twentieth century a power structure between London and New York which penetrated deeply into university life, the press, and the practice of foreign policy.”[20] Its outlook, in somewhat disorganized form, involved a generic vision of world federalism led by British liberal values, extending from the Empire to the formation of what became the Commonwealth of Nations, in the initial organization of which members of the Milner Group played an out-sized role. Quigley alleged that in the 1920s and 1930s, at the apogee of this Anglophilic global cultural network, “Christian Science became the religion of the Milner group.”[21] The group’s ideals partly carried over after World War II into the New York-based United Nations, World Bank, and North Atlantic Treaty Organization among other initiatives at linking international networks, in what became the origins of formal globalization, in which the liberal Presbyterian Dulles was a key player. At the core of Milner Group efforts, which Quigley ultimately deemed unsuccessful in terms of its own Anglophilic vision, lay three prominent British Christian Scientists, politicians, and influencers, Lord Waldorf and Lady Nancy Astor, and Lord Lothian (Philip Kerr), the latter becoming British Ambassador to the U.S.

Of the Royal Institute for International Affairs/Chatham House, and its influence spreading out from the Milner Group to aspects of British and Commonwealth policies and the U.S., as well as involvement of academics in the Group such as historian A.J. Toynbee with his British intelligence connections, Quigley offered an extreme cautionary note, which became the fodder for later conspiratorialists despite his qualifications: “No country that values its safety should allow what the Milner Group accomplished in Britain—that is, that a small number of men should be able to wield such power in administration and politics, should be given almost complete control over the publication of the documents relating to their actions, should be able to exercise such influence over the avenues of information that create public opinion, and should be able to monopolize so completely the writing and the teaching of the history of their own period.”[22] Quigley himself discounted extreme conspiracy theories about the group. But having claimed to have had access to archives of the network, did conclude it represented an influential private actor in elite culture and policy globally for a few decades.

Doris Day with Jimmy Stewart as they worked together on the 1956 classic Hitchcock thriller The Man Who Knew Too Much. Day was a kind of cultural icon for Christian Science in American civil religion.

In any case, the history of Christian Science suggests the apparent mutual attraction between global power, spirituality, and utopianist hopes, contributing to the atmosphere of a more general globalist civil religion that reached a new high in the Dulles era. But, Fraser noted, Christian Science’s influence came at spiritual, physical, and psychological costs to many individual adherents. One example is the literal poster person for Christian Science in 1950s America, the singer and actress Doris Day. Her wholesome and “all-American” positive image seemed to personify the faith, her commitment to which was widely known publicly. However, beneath that facade, biographical details of Day’s life indicate how the faith had led her to a challenging marriage with a fellow adherent, her manager Martin Melcher. His untimely death under Christian Science care led to revelations of extensive debts and performance contracts that he had arranged under her name but had hidden from her.[23] Melcher’s death and subsequent revelations led to Day’s estrangement from the Hollywood Christian Science healers who had supported her faith. She later wrote of how a physician helped her overcome anxiety she could not handle in Christian Science, through simple breathing techniques. She said she came to regard Christian Science as a positive-thinking philosophy that she still, like many Americans, found appealing and followed in a general way, although outside the formal denomination. Many Hollywood stars and other public figures like Day had relations with Christian Science that were of varying degrees of involvement and continuity. Their celebrity lent glamor and credibility in popular culture to a faith that was also operating often at high economic and political levels, with an all-American image. But a growing number of recent memoirs from former Christian Scientists who were never celebrities also attest to psychological and medical costs from their involvement, and accounts of children dying under Christian Science care and resulting legal cases gained increaed media attention in the late twentieth century.

To return briefly to power aspects of the cult, the Nixon administration’s influence on globalism in establishing American relations with Communist China, in going off the gold standard of the Bretton Woods system, in withdrawing militarily from Vietnam, and other policies, is well known. While such efforts may primarily be attributed to Nixon and his foreign policy czar Henry Kissinger, and the support of expansionist economic interests from Wall Street and corporate sectors, they were also in keeping with the globalistic spiritual sensibilities of the Christian Scientists who served Nixon as key advisers, while echoing earlier efforts at Anglocentric globalization (critics would call it neocolonialism) dating back to the Milner Group. There was no one simple political model behind this, but more a cultural influence. Yet following Watergate, and with the denomination’s demographic decline, Christian Scientists played a greatly diminished role in the halls of power, and by the second decade of the 21st century none remained in the U.S. Congress. Christian Scientist Henry Paulson’s career of developing closer U.S.-China finance ties on Wall Street in the 1990s and then in leading the U.S. Treasury in the 2000s, however, suggests a continuing affinity between the old spiritual culture of Christian Science and later Anglo-American-led globalism. For those nostalgic for American “old-time” religion, yet swept up in technological progress and worldly careers with modern cares and stress, Christian Science apparently offered a bridge to a new imagined landscape of global spirituality, with a bit of biblical garnish and (however heretical) seeming rigor.

Christian Science as a cult never officially became one of the “Seven Sisters” of Mainline Protestantism during the Dullesian Cold War “Great Awakening” of civil religion. But it often presented itself aspirationally as such, and to a degree was partially so accepted. But one of the actual “Seven Sisters,” pillars of the upsurge of civil religion, hosted a cult that came to represent perhaps the most notorious example of Hieromonk Seraphim’s “religion of the future” at odds with Orthodoxy, namely the People’s Temple in the Disciples of Christ. The latter time-honored American Protestant denomination had been the religious home separately both to President Ronald Reagan and to the mass-murderer Rev. Jim Jones.

JONESTOWN’S ROOTS IN THE “SEVEN SISTERS” OF AMERICAN CIVIL RELIGION[24]

In 1978, Rev. Jim Jones led more than 900 followers to their deaths in the jungles of Jonestown, Guyana by having them drink poisoned juice. It was one of the darkest days of the revolutionary after-life of the 1960s in America. Yet it arguably had roots in the same cultural mix as the “Great Awakening” of American civil religion in the 1950s, though a 2.0 “next generation” version gone badly wrong. His congregation, called the People’s Temple, had flourished in the San Francisco area with strong connections to West Coast and even national liberal political leadership, including figures such as northern California political boss Willie Brown (who helped lead the legislative effort to legalize homosexuality in California in the 1970s) and the controversial LGBTQ+ icon Harvey Milk. Jones’s career as a socially activist Protestant pastor in the Disciples of Christ had brought him from Midwestern obscurity to a position of influence, wealth, and power in a relatively short time.

Above) Rev. Jim Jones of the Mainline Protestant Disciples of Christ.

But Jones also was an avowed Marxist-Leninist operating in Mainline Protestantism, who wanted to move his community to the Soviet Union, clearly different from Dulles and his generation, and many Mainline Protestants of course in his own generation. He called himself a reincarnation of Lenin as well as Jesus, while fomenting anti-Christian actions by his followers such as using Bibles for toilet paper, and identifying God as Principle or Love equated with communism. His community grew out of the hopes and tarnished idealism of what had been the California of Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, a California in many ways a 1950s stronghold of the Dulles-Eisenhower civil religion and of Christian Science and a national place for “second chances,” but begetter in the next generation era of Jones also of the Summer of Love, the Black Panthers, the Symbionese Liberation Army, and the Zebra and Zodiac killers.

The links from Jones back to the 1950s civil religion of Dulles may seem invisible, but aspects of religion as a national focus for political action, spirituality as a source of personal identity involving sexual and racialist aspects, of a Christianity increasingly removed from traditional culture and Trinitarian-Incarnational historical culture, and positive willpower as a vehicle for self-improvement in one’s personal life and career, were elements reflected in Jones’ group, but in a more extreme and autocratic form. The Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt described cultural atomization, isolating people in a social mass including both elites and lower-class mobs, as a sign of a totalitarian movement.[25] Jones’ large Disciples of Christ congregation fit that bill, drawing in part on earlier and twisted aspects of development of Mainline Protestantism into an American social as well as civil religion, along with influences from cultural Marxism.[26]

To Jones, religion was a cloak and vehicle for socialist revolution, although his approach was in some ways the Social Gospel run amuck. Belonging to the Disciples of Christ, Jones’s church picked up on rhetoric of the civil rights movement, bought a large former Christian Science church in Los Angeles for its southern Californian hub, and became its denomination’s largest congregation. Like the positive-thinking cult prominent in 1950s American civil religion, although operating in a different dimension for a new generation, it claimed to offer a transformation of self in social communion. Deborah Layton Blakey, a top member of the People’s Temple who escaped, testified (in an affidavit that prompted Ryan’s fatal visit) to the cult’s appeal:

I was eighteen years old when I joined the People’s Temple. I had grown up in affluent circumstances in the permissive atmosphere of Berkeley, California. By joining the People’s Temple, I hoped to help others and in the process to bring structure and self-discipline to my own life.[27]

She wrote in her memoir of her own suffering of physical, mental, and sexual abuse at the hands of Jones in the name of the revolution.

An entrance to the Jonestown community in Guyana.

But until its tragic and sickening end, Jones’s community remained in the Disciples of Christ, in which his community was also a congregation, originally drawing on a shared legacy of the Social Gospel movement with which Dulles’ family had been involved. Jones’ cult paralleled certain elements of the Dulles-Eisenhower civil religion of a generation before, but in a more nihilistic key: A Manichaean view of good versus evil, a total lack of traditional ecclesiology resulting in extreme autonomy for the leader to impose his will, a devotion to social and political activism, an internationalist orientation (seen in Jones’ relation to the socialist regime of Guyana and devotion to the Soviet Union), a utopian sense of exceptionalism (in this case in belief in the community as a new vanguard of American society), and development of a vague theology ultimately idolizing human will to power. This in many ways flipped around the earlier American civil religion, but arguably as a fractured mirror held by a new generation. Jones’ was the destructive next generation of an ever-changing civil religion, reflecting Dostoevsky’s view in his novel Demons that the idealists of one generation beget the nihilists of the next, and pointing to its end trajectory.

If Jones’ cult emerged from hyper-social activism, it drew in this on a theologically vague sense of Deity identified with social and sexual love. Self-emptying in Jesus Christ was replaced by an individualistic American identification with passions, and an emphasis on meeting material needs and wants, expressed under a tyrannical social-activist and abusive leader. Its cult of self-will arguably exploited flaws of the civil religion in the 1950s. In the absence of tradition, it tended to exalt personal will while ironically making people more submissive to social control, “atomization” in separation from tradition, to use Arendt’s term for a precursor of totalitarian culture. Jones combined a racialist and pan-sexualist political machine with a religious cult, by harvesting votes for San Francisco political leaders to help their careers and spread their post-1960s ideologies. This further version of civil religion as worldly power was not so much an atheistic revolutionary ideology as (in its emphasis on will) a new kind of pagan challenge to what John Adams (himself a Unitarian albeit one rooted more historically in historic Protestant faith) once called the “general principles of Christianity” underlying America and the traditional Christian sense of family. A racialist exalting of “people of color” mirrored the Anglo-American racialism of Christian Science Gnosticism with its British Israel orientation. It also echoed the latter’s idolizing of comfort exemplified in physical healing and economic success. The earlier emphasis on willpower was hijacked into identification with socially destructive passions, including abusive and perverse sexual behaviors.

In the 1970s, support from political leaders enabled Jones to grow his pioneering mega church in San Francisco, where he had moved it from Indiana. Willie Brown, a former California Assembly speaker and San Francisco mayor, who later would become former U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris’ boyfriend and political mentor, reportedly attended Jones’ Peoples Temple several dozen times and praised Jones liberally. Brown introduced Jones at a testimonial dinner positively as “a combination of Martin King, Angela Davis, Albert Einstein … Chairman Mao.” Brown’s flippancy about Mao, allegedly the greatest mass-killing leader of history, became more chilling given Jones’ finale, the greatest cluster of forced civilian deaths of Americans prior to 9/11. San Francisco Mayor George Moscone appointed Jones chair of the city Housing Authority Commission. LGBTQ activist Harvey Milk spoke often at Jones’ congregation, saying he found there “a sense of being … I can never leave.”

With Jones as an ally, Brown not only spearheaded legalizing homosexuality in California, but built his political clout in what became in San Francisco ground zero for a later version of American civil religion, popularly known as “wokeness.” This de-Christianized civil religion by 2020 was playing a dominant role in U.S. culture, identifying man with passions and the divine with a love defined socially and sexually in quasi-communist terms rather than Truth as Jesus Christ. The new quasi-religious “awokening” rooted in the 1960s sought to override the “laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” cited in the Declaration of Independence, in its own transcendent social vision. Brown disavowed Jones after the tragedy at Jonestown. But both had shared the ultra-racial and hyper-sexual reinterpretation of what it means to be human that bloomed among northern California leftists in the late 20th century, a culture hostile to what Abraham Lincoln called “one nation under God” and the Declaration’s view that rights come from God in a Christian context. It was a culture identifying people with their passions, their wills with a vague Deistic force, not the traditional Trinity, and exalting the sin of “Pride.” Jones had decided early in his career that as a revolutionary it was not profitable to continue in the Soviet-allied American Communist Party (whose goals included, following The Communist Manifesto, undermining traditional family), because it was dogged by an anticommunist FBI. So, he decided in effect to hide in an establishment American Christian group, becoming a pastor in the Disciples of Christ.

The new culture of spirituality behind radical politics in northern California, exemplified by Jones in extreme, just as Dulles a generation before had personified an older version of civil religion, aligned itself with a worldly view of human beings categorized by skin color (the mystical unity of “voices of color”) and preferred sexual orifices and stimulation, in an identification again of self with prideful passions. Yet this ideology also paradoxically presents identity as fluid, unbound by objective limits, except again self-willed racial and sexual identities, linked to aspirations of worldly success. In this way it was both far and near from the Disneyesque positive thinking of a generation before, offering its own version of both a “small world” and “carousel of progress,” but nightmarishly for traditional Christians.

To be sure, many Americans, while horrified by the denouement of the Jones mega-church, did not see the genealogy from civil religion of the 1950s to New Age activism by the 1970s, and “woke” faith of the 2010s and later, or if they did would not accept it as a negative. Just as the early form of civil religion had a positive optics of uniting the country against Communism, so later developments of civil religion often were seen as marking social progress toward first equality and then equity among all people. Yet Orthodox Christianity would share the critique of St. Athanasios Pairos of the French Revolution, that the freedom and equality involved were worldly delusions and distractions from salvation in the Orthodox Church, observing that the movement of elite American culture and institutions further away from traditional Christianity had roots in deeper and older theological flaws already discussed. At the same time, the 1960s through 1980s have been termed a time of another “great awakening” of evangelical Protestantism in a different dimension, toward a more socially conservative view of society in the new “Christian Right.” Yet this too showed echoes of the earlier Dulles-era civil religion: Identification with worldly political goals, of a self shaped in issues of willpower and success with potential slippage toward worldly comfort, of a Manichaean good versus evil in terms of self and other, and of a lack of traditional theological rigid. (There were other sides of this story of a renewed awakening of Christian faith in America, albeit heterodox, of course, including threads that led toward Orthodoxy through the missionary work of Hieromonk Seraphim and others.)

Orthodox Christian culture as articulated by Hieromonk Seraphim afforded an outside perspective on events culminating in Jonestown, in theologically based critiques of developments in modern Western culture that extend back to insights on the French Revolution already described (bearing in mind always the sins of us Orthodox as well, myself more than all). The late Dartmouth poet Donald Sheehan, an American convert to Orthodoxy, said the lesson of the great novels of Dostoevsky — a writer obsessed with nihilism’s advance in the West, satirized in his classic Demons — was the need for self-emptying in Christ rather than self-assertion.[28]

Fyodor Dostoevsky, a leading Orthodox Christian critic of the modernity of the global West, often labeled a “Christian existentialist” in the West. He also was a prime inspiration of Russian Orthodox writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s similar critiques.

Indeed, amid all the self-willed identity power in America’s latest generations of civil religion, both on the radical Left and the careerist Right, the command by Jesus to love our neighbor more than our self (in His New Commandment) would seem lost. In The Gulag Archipelago, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, himself a literary and philosophical acolyte of Dostoevsky, summed up three basic principles of Bolshevik atheism that oddly mesh with the self-assertion of today’s globalizing ethos:

1. Survive at any price. The ends justify the means, even the death of others.

2. Only material results matter. Two wrongs can make a right.

3. Adherence to the “permanent lie.” Don’t disturb the virtual reality in which we all supposedly must swim, lest you disturb your career and loved ones.[29]

Arguably, these rules (paralleling similar observations by the Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt about modern totalitarian cultures at large) influenced 21st-century American civil religion under both the banners of social justice and careerism, neo-Marxism and neoconservatism. At an extreme, Jones blasphemously turned the image of Christian eucharistic participation into mass suicide-murder, with loudspeakers blaring messages and music. But today, expressing self-will for power often accompanies submitting to false unity in secular virtual reality, as if in a new godless liturgical rite involving smart phones that increasingly control us and motivate us to cycles of consumption and activism, now powered with AI. For example, the live-streamed body of Dionysus at the opening globally streamed Olympic rituals in Paris in 2024 offered a blasphemous LGBTQ-inspired parody of the Last Supper, attended by world elites, and viewed online by a large part of the earth’s population as a kind of global festival rite. Hieromonk Seraphim Rose wrote in the 1970s of how a new religious spirit was at work, permeating all sides of American politics. Today, people increasingly live online, again via AI, in a virtual version of Creation, which often we look right through without seeing, as C.S. Lewis foretold in his The Abolition of Man, in distracted and even potentially demonic states of delusion. A virtualized global civil religion 3.0 exemplifies Hieromonk Seraphim’s prophetic concerns about a “religion of the future” at odds with Orthodoxy.

As a boy, I remember watching TV news of the massacre at Jonestown in our modest neighborhood in Chicago’s bungalow belt, feeling in Shakespeare’s words as recycled by Ray Bradbury that “something wicked this way comes.” Jones had directed the killing of investigators including my own cousin, U.S. Rep. Leo Ryan. Ryan grew up with my father in a now-vanished West Side Chicago Irish-American enclave. The two went on double dates in high school. I have an early home movie of them wrestling on an inner-city lawn, leftover from an earlier American Dream. But the images on TV news of the destruction of Jones’ Disciples of Christ community, again the largest congregation of that member of the Seven Sisters of Mainline American Protestantism, were apocalyptic. Going beyond Jonestown and across subsequent generations, a new virtual-reality civil religion as a media system arguably has immersed us online in a new normal. The online world generally defines the traditional as “weird,” synonymous with creepy. But once “weird” meant having an otherworldly destiny. Indeed, traditional Christianity and ideas of self-government that emerged from it have always been “weird” in the older sense. The memory of Jonestown, and the recent live-streaming of the neopagan global Dionysus satire of the Last Supper from the Paris Olympics, by contrast warn Orthodox Christians of today’s danger of normalizing the diabolic in the Global West. For Orthodox Christian faith, however, this live-streamed revolution will not be the last word, thank God. This is taught us in Church Tradition of the Apocalypse, the final book of Scripture, to which we will now briefly turn in conclusion.

TO THE CHURCH OF PHILADELPHIA: WARNING OF GLOBALIST APOSTASY